Translate this page into:

Clinical recovery in a patient of Neuromyelitis Optica with Spinal Cord Atrophy- A Case Report

Corresponding author: Nigarbi Ansari, Response Plus Medical. Former Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Seth G. S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, Mumbai, India Email ID - nigar8193@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) spectrum disorder is a chronically relapsing autoimmune astro-cytopathy mainly affecting optic nerve, spinal cord and brain stem. With newer treatment modalities, the clinical course of the disease has changed significantly. Our patient, 30-year-old female first presented in Jan 2023, with low back pain and numbness below the level of umbilicus followed by weakness of the lower limbs over the period of 7 days. She also complained of bladder and bowel incontinence, besides there were no cranial nerve or upper limb involvement. Patient’s Magnetic Resonance scan (MR Scan) suggestive of patchy T2 hyperintense signals from thoracic vertebral level D3-D9 with myelomalacia. She had previous 3 attacks of acute myelitis in the years 2012,2017 and 2018. Her cerebrospinal fluid study was positive for Aquaporin 4 antibody, confirming the diagnosis NMO in 2012. She showed clinical improvement with steroids and tab Azathioprine. Patient had relapse in 2017 & 2018, for which she received 5 and 4 cycles of plasma exchange therapy respectively with significant improvement. Due to earlier response to steroids, patient was started on Injection Methyl Prednisolone with minimal improvement. Hence, patient was given 5 cycles of Plasma Exchange with high clinical suspicion of recovery. She responded to the extent that she was able to walk with support by day 15. However, repeat MR scan suggestive of persistent spinal cord atrophy. In summary, with high clinical suspicion and timely intervention with plasma exchange therapy in Neuromyelitis Optica, patient can have clinical improvement even in spinal cord atrophy.

Keywords

Neuromyelitis Optica

NMO

Spinal cord atrophy

Plasma exchange

INTRODUCTION

Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) is a rare chronically debilitating condition presents with repeated autoimmune inflammation affecting spinal cord and optic nerve. It’s also known as Devic’s Disease or Devic’s syndrome after the name of Dr. Eugene Devic, who first described the condition in 1894, in a patient with optic neuritis with neuromuscular involvement.1

Patient Information

A 30-year-old married female presented in January 2023, with low back pain and band like sensation around her umbilicus. She noticed tingling sensation in bilateral lower limb which worsened to complete loss of sensation below the level of umbilicus over a period of 7 days. This was associated with difficulty in lifting the lower limb above the level of ground. Subsequently, she developed urinary and fecal incontinence. Besides, she did not complain any upper limb weakness, blurring of vision or respiratory discomfort. There was no prior history of fever, gastroenteritis, or vaccination.

Clinical Findings and Diagnostic Assessment

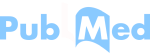

On clinical examination, patient was conscious and alert. Hypotonia was present in both the lower limbs. Power in the lower limb was MRC grade-1, reflexes were absent. There was complete loss of sensation below the level of umbilicus. She was evaluated with differential diagnosis of Acute Transverse Myelitis, Multiple Sclerosis, SLE Myelitis and HIV. Her routine blood investigations along with autoimmune profile and HIV serology were negative. MR Scan was suggestive of long segment T2 hyperintensity in the spinal cord extending from Dorsal spinal level 3-9 with volume loss and myelomalacia suggestive of spinal cord atrophy (Figure 1). CSF analysis was insignificant. Her Fundus examination and Visual Evoked Potential were normal.

- MRI Spinal Cord: Long segment T2 hyperintensity in the spinal cord extending from D3-D9 levels with volume loss and myelomalacic changes suggestive of spinal cord atrophy (long arrow). Atrophy at cervical region. (Short arrow)

PREVIOUS HISTORY

Patient initially presented in 2012, with low back pain, tingling sensation in lower limb along with paraparesis. There was associated bladder bowel incontinence. MR scan at that attack was suggestive of lesion-1 patchy T2 hyperintense signal from D2-D10 level with dilatation of central canal in upper dorsal region with subtle enhancement. Lesion-2 patchy signal abnormality at C4-5 level along with cord oedema. Her Anti-Aquaporin-4 Antibody (AQPA-IgG) was positive. She was diagnosed as NMO with optic nerve sparing and was started on injectable Methyl Prednisolone (MPS) 1gram for 5 days. This was followed by tapering dose of oral Prednisolone (1mg/kg) for 4 weeks along with tab Azathioprine (50mg) three times a day. Her clinical condition improved significantly.

Patient was compliant to the medication and completely asymptomatic till 2017, when she developed pulmonary Tuberculosis. This was associated with lower limb tingling sensation and weakness. She was started on Anti-Tubercular medications for 6 months. She was diagnosed with relapse of NMO secondary to infection and was given 5 cycles of Plasma Exchange therapy. Tab Azathioprine was stopped and she was started on tab Mycophenolate Mofetil 500mg three times a day along with oral steroids. Her clinical condition improved. She again had relapse of NMO in 2018, for which 4 cycles of Plasma Exchange were given.

Therapeutic Intervention and outcome

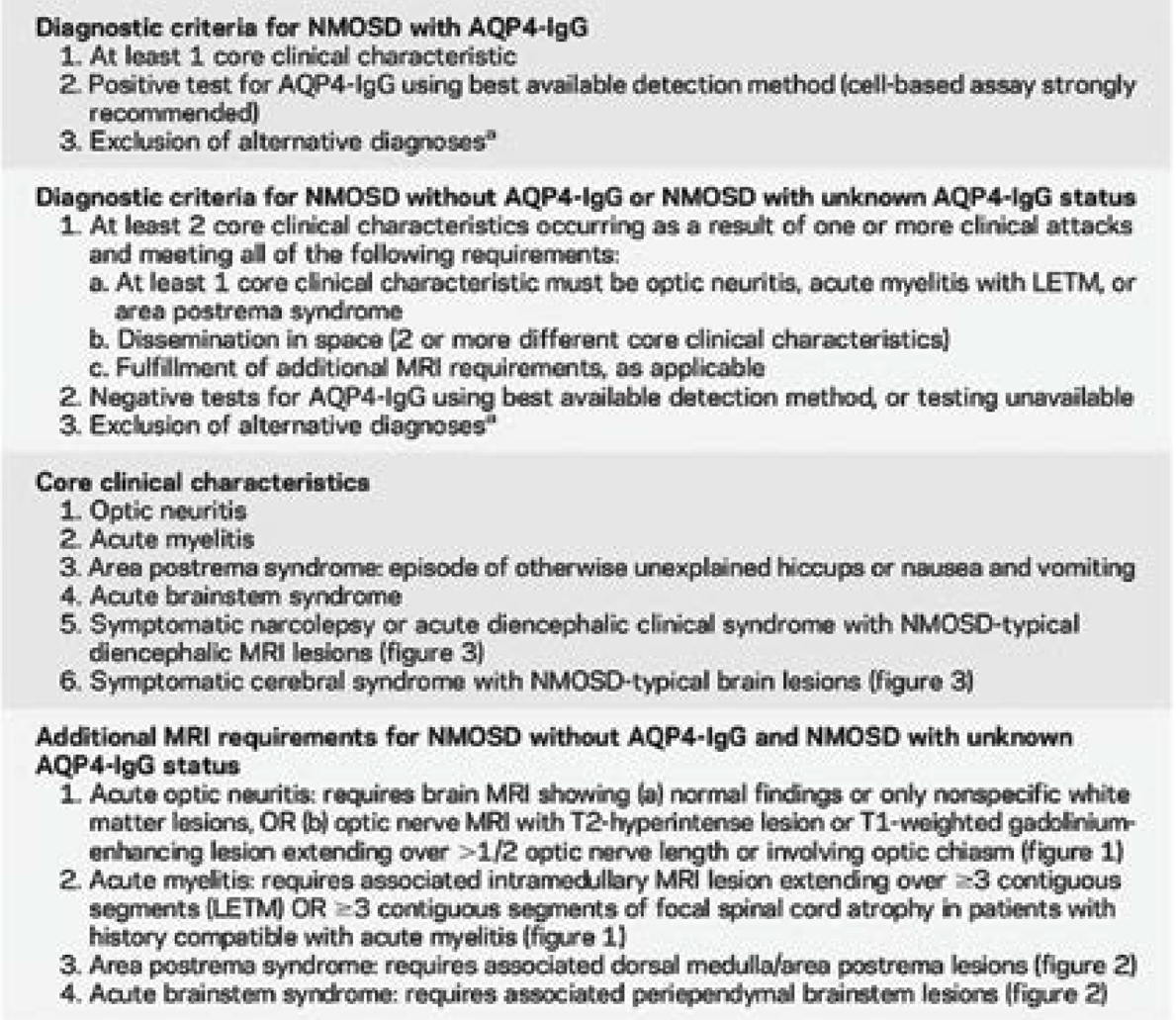

With the history of initial response to steroids, injection MPS (1gm for 5 days) was administered to her for current relapse as well, but there was no clinical benefit. With spinal cord atrophy in the patient, the chances of improvement were uncertain. However, patient was given 5 cycles of Plasma Exchange (PLEX) therapy in anticipation of recovery. Her power improved after 15 days of starting PLEX therapy, however the atrophic changes on the MR scan were persistent (Figure-2). On follow up visit patient could walk independently.

- MRI Spinal Cord: T2 hyperintensity from D3-D9 without post contrast enhancement with myelomalacic changes. (Arrow head)

DISCUSSION

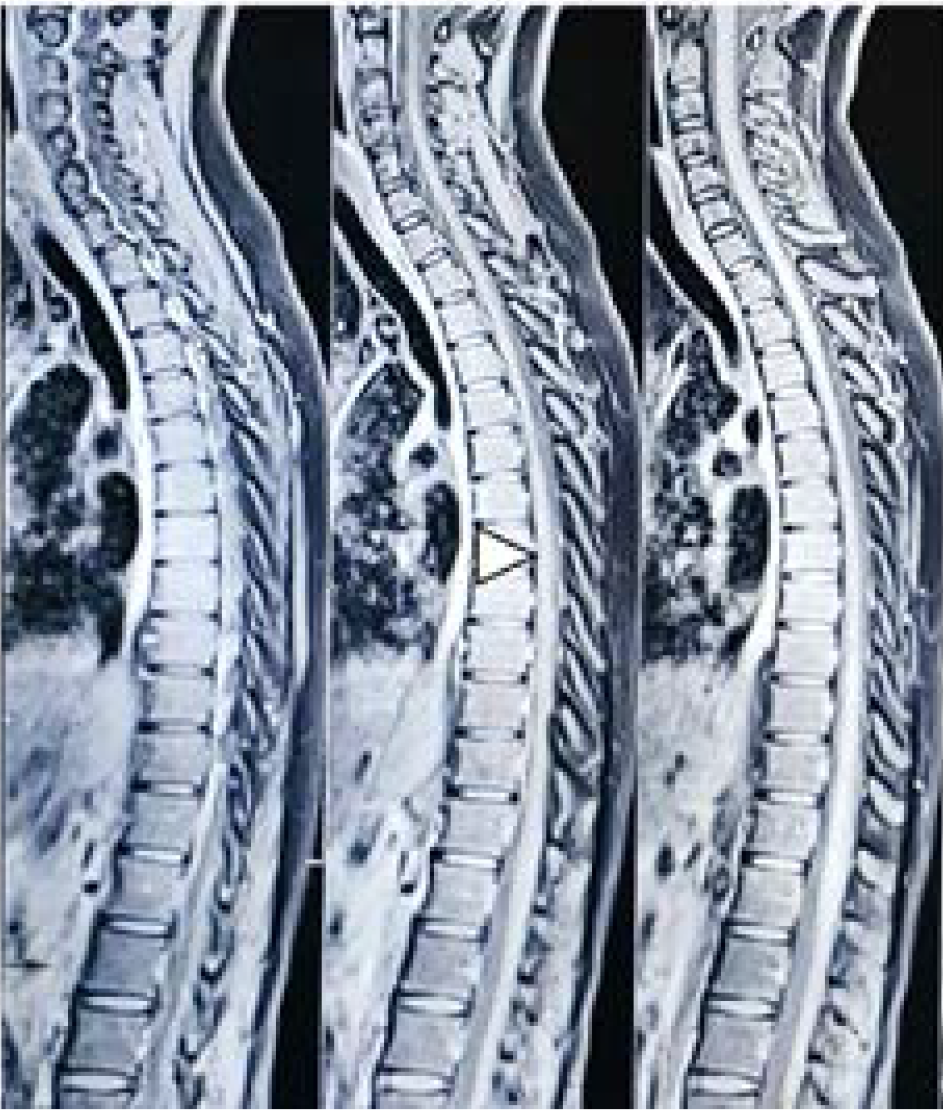

NMO is a rare autoinflammatory disorder mainly presenting with recurrent attack of optic neuritis and myelitis. The incidence of the disease ranges from 0.05-4.4 per 100,000.2 Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD) is a more comprehensive term, based on presence of AQP4 antibodies, which include the patients with partial disease and also those who have additional region involved in the CNS. A diagnosis of NMOSD is now made using the “International Panel for NMOSD Diagnosis (IPND) Diagnostic Criteria 2015” (Table-1).3

|

NMOSD occurs more frequently in women.4 The mean age of onset is 39 years; however, the disease may also occur in children and in the elderly. 4 The disease could be a monophasic (10%) or relapsing disease (90%).5 The presence of Aquaporin4 antibodies highly correlates with the multiple relapses in the disease course.5,6

Peripheral AQP4-IgG react with AQP4 in astrocyte feet, along with the activation of complement, to produce complement dependent cytotoxicity.6 AQP4 has been found in a high percentage (~75%) of NMO patients (NMO-IgG).7 Other autoantibodies have been found in NMO patient sera and CSF, including antinuclear antibodies, SS antibodies and in particular anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies.7,8

Patients with NMOSD presents with recurrent attack of paraparesis, quadriparesis and involvement of optic nerve leading to either unilateral or bilateral vision loss. However, minority of the patients can also present with symptoms affecting other areas of brain. Untreated disease is usually quite disabling over the period of time. However, with newer diagnostic modalities and available immuno-suppressants, the morbidity of the disease has reduced significantly. Spinal cord lesions usually extend over three or more segments in patients with NMO may or may not be associated with atrophy. The prevalence of SCA was 57% in Cassinotto Cet al. study.9 In our case report, patient presented with 4th attacks of acute myelitis with optic nerve sparing.

Management for NMO consists of treating the acute attack, prevention for future relapses and treatment of the residual disability. Acute treatment for the relapse includes high dose of corticosteroids (1000 mg of Injection MPS for 5 days), followed by an oral steroid taper for 2–8 weeks.10 If there is minimal or no improvement with high-dose corticosteroids based on the judgment of the treating physician, the use of 5-7 cycles of plasma exchange (PLEX) has been shown to be effective in NMOSD.11 Intravenous IVIg has been used for resistant cases with minimal benefits. Preventive strategy for further relapse includes Azathioprine, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Rituximab. Novel monoclonal antibodies like Eculizumab, Inolimomab and Satralizumab are under trial for add on immunosuppressive therapy.11

Our case report focusses on the use of PLEX therapy for the patients of NMOSD with spinal cord atrophy. Patient was nonresponsive to high dose of corticosteroids. With severe spinal cord atrophy and myelomalacic changes on MR scan, there was a therapeutic dilemma to give PLEX therapy to the patient. However, with timely intervention and accurate decision, patient was started on PLEX therapy and there was significant clinical recovery.

CONCLUSION

PLEX therapy could be beneficial for the patient with spinal cord atrophy in NMOSD along with high dose of corticosteroid and rehabilitative measures.

END NOTE

Author Information

Nigarbi Ansari, Response Plus Medical, Seth GSMC & KEM Hospital Mumbai, India Anjali G Rajadhyaksha, Seth GSMC & KEM Hospital Mumbai, India Meghna Vaidya, Seth GSMC & KEM Hospital Mumbai, India Vedant Chate, Seth GSMC & KEM Hospital Mumbai, India

Conflict of interest

None declared

References

- Neuromyelitis optica (NMO devics disease) InStatPearls [Internet] 2022. StatPearls Publishing;

- [Google Scholar]

- International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177-89.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Clinical Neuroimmunology: Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2011:219-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care 1992 Jun 1:473-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular pathogenesis of neuromyelitis optica. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13(10):12970-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005 Aug 15;. ;202(4):473-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuromyelitis optica and non-organ-specific autoimmunity. Archives of neurology. 2008;65(1):78-83.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MRIof the spinal cord in neuromyelitis optica and recurrent longitudinal extensive myelitis. J Neuroradiol. 2009;4:199-205.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasma exchange in severe spinal attacks associated with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2009;15(4):487-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monoclonal antibody-based treatments for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: from bench to bedside. Neuroscience Bulletin. 2020;36:1213-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]